by Meteorologist, Kerry Challoner Anderson

“I can say without any dramatization whatsoever: If you choose to stay in one of those evacuation areas, you’re going to die,” This was the message delivered by Jane Castor, the major of Tampa, as Hurricane Milton was making a beeline for her city. With Milton now in the rearview mirror, this statement has proven to have been an overdramatization. People did stay and didn’t die. As I listened to this dire warning, I cringed because though it was only intended to preserve life, the message was inaccurate.

I have been a meteorologist since the 1980s and I have delivered my fair share of warnings. That is part of the job. It is gut-wrenching to tell a city that everyone should close their businesses and head home to shelter from a storm only to sit and wait and hope it materializes. If it does, you are the hero and if it doesn’t, then you are mocked. If buildings are destroyed and people die then people are more likely to listen next time but if nothing damaging happens then people are less likely to heed the warning next time. As you can imagine the story of the boy who cried wolf is well known in meteorology circles.

Meteorologists are the first to admit that the science is imprecise, though it has improved incredibly during the decades since I started working. Our models are gaining accuracy and I have been amazed to see predictions 5 days out accurately locating landfall. However there is still too much data and too many variables for our models to be able to forecast for every spot with pinpoint accuracy. So we recognize that when it comes to major storms we have to give broad and large warnings in the hopes that everyone has a chance to shelter and save their lives and property. Consequently, this means we overwarn.

I have listened to many debates in meteorology circles on how we balance the need to warn without over warning and creating fatigue. Right now I am visiting family in Oklahoma and at the bus stop I was talking to parents from the neighborhood. They told me that when the tornado sirens go off they grab a soda and go out on the patio to watch. None of these people have encountered a tornado so they have become lax in heeding the warnings.

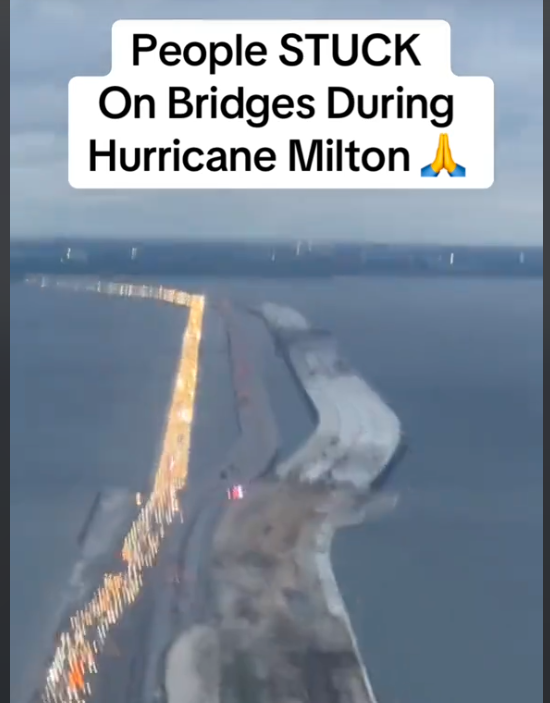

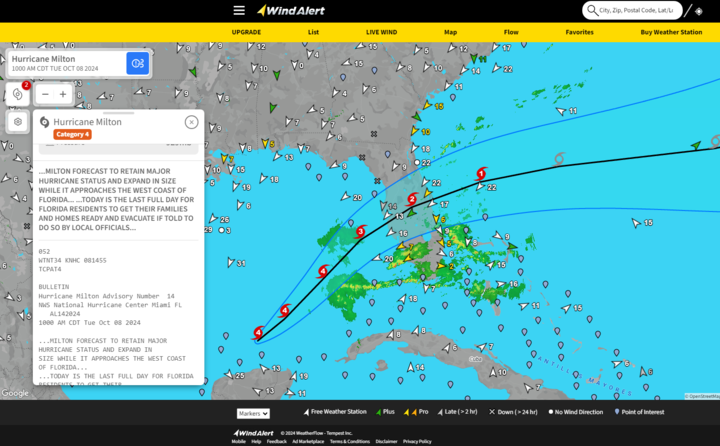

But let’s get back to Milton. Put yourself in the shoes of the emergency managers. Milton rapidly intensified. It reached a minimum central pressure of 897 millibars, making it the fifth-most intense Atlantic hurricane on record. You need 2-3 days to evacuate all the people in the area. When do you make the call to leave? If you wait too long people can be stuck in gridlock all trying to leave at the same time.

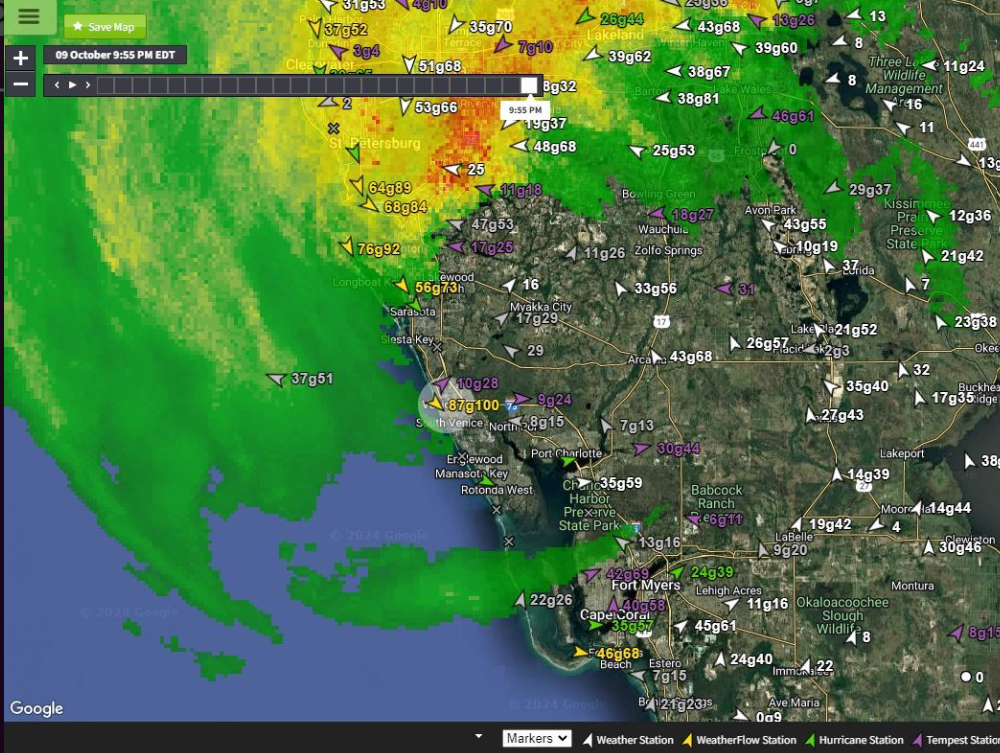

Milton didn’t pan out quite as expected. In the last 12 hours before it hit Florida it encountered an area of shear and dry air wrapped into the storm making it lopsided. Consequently, the right front quadrant of the storm weakened and the storm surge was not as high as had been expected in the Tampa area. The storm did pack a punch though and was deadly. 25 people died as a consequence of the high winds, flooding and tornadoes that this storm produced.

So did the emergency managers make the right call? Some would say yes and others no. Some returned home to find all well and might not evacuate next time. But many others returned to find their homes flooded and are happy they were able to ride the storm out from a safe distance. Meteorology is an imprecise science and we won’t get all the warnings right but heeding those warnings may just be the difference between life and death.