By Matt Souders & Mike Godsey

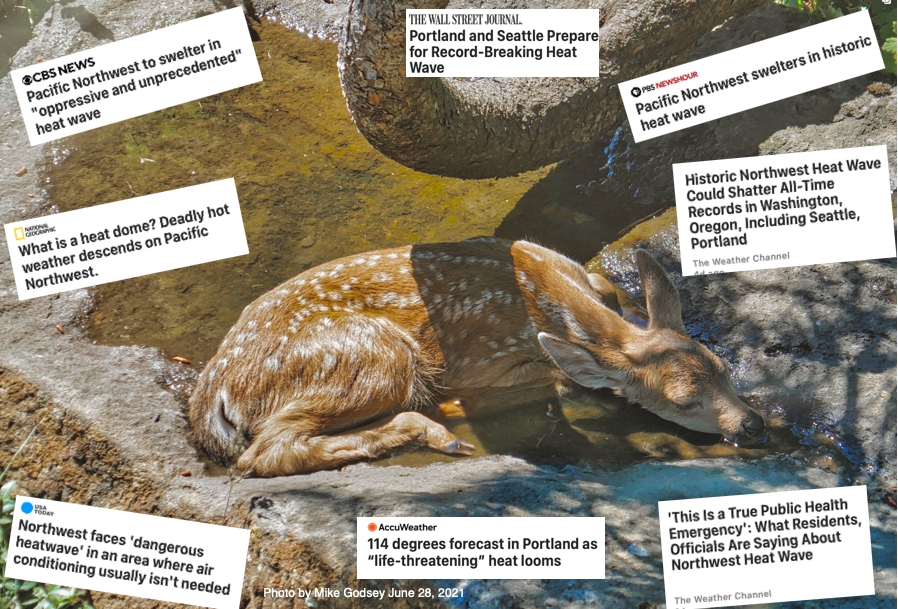

Look at the headlines below and the fawn seeking refuge at Mike’s house from the Pacific Northwest’s worst heat wave since the 19th century. How did we get here?

Well, it starts with warming high in the atmosphere. The jet stream is a belt of fast west winds that blow around the world at about 30,000 feet aloft. These upper level winds also meander north and south while storms travel with these winds.

Nature’s mixers

Storms are like nature’s mixers – they pump warmer air north ahead of them and drag cooler air south behind them. If you get a few large storms in a row heating the same area, you get a massive dome or bubble of air that’s warmer than the surrounding air. These domes are called upper ridges.

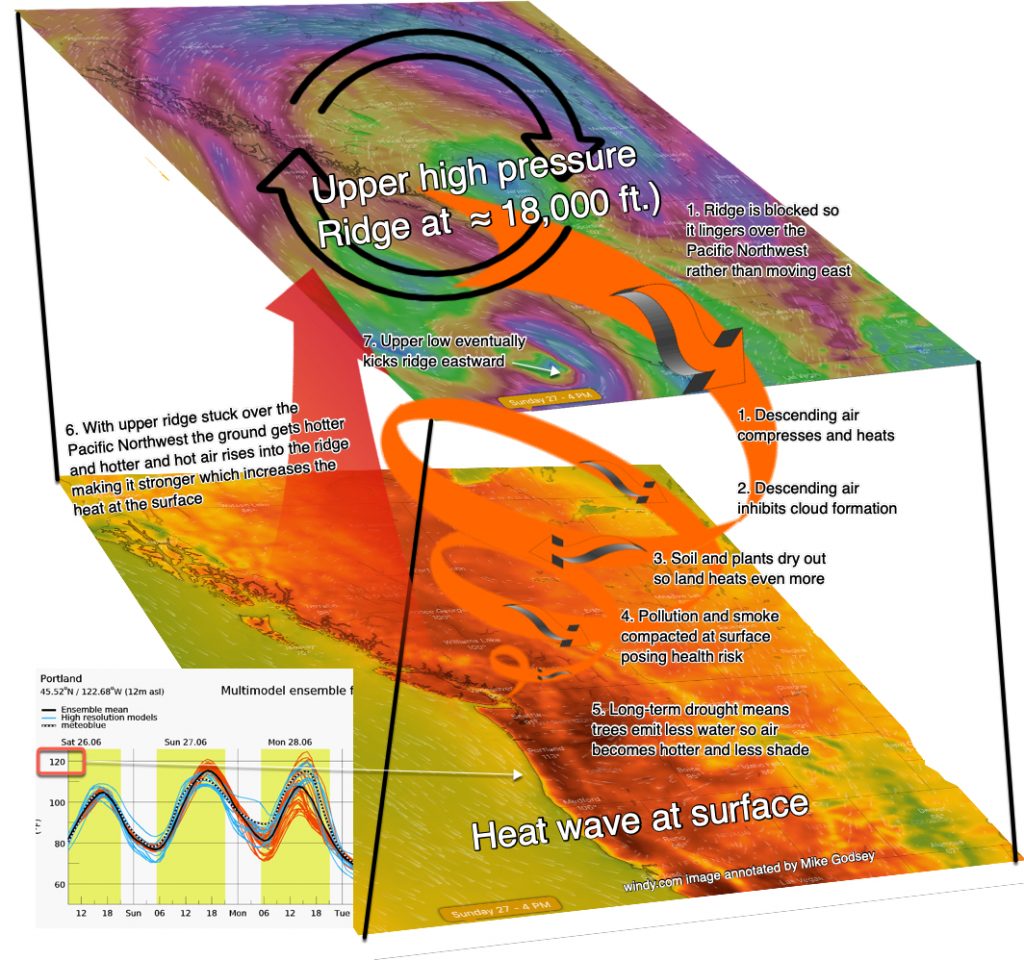

Below, you can see a large upper-trough over the central Pacific. And over the Pacific Northwest our blocked upper-ridge.

Upper Trough & Upper Ridge

Pacific trough storms helped strengthen this upper ridge over the last several days as we described above. But why is this particular ridge making it so much hotter than usual?

Drought

First, the Pacific Northwest is suffering through a long-term drought and this past spring was one of the driest on record. If the ground is moist, it doesn’t get as hot on a sunny day because some of the sun’s heat gets spent turning that water into water vapor. We started June with dry ground and it has only gotten drier. With less evaporation, the air gets even hotter.

Blocking

Second, the upper ridge is blocked. Normally, ridges and troughs in the upper atmosphere move west to east steadily. As they move, they heat up a different patch of the surface each day or two. This limits the heating.

But, if a ridge is blocked, it heats the same patch of ground several days in a row. Then, the overheated ground heats the air in that bubble more and more, making the ridge stronger. It’s a vicious cycle if something doesn’t come along and break the logjam.

The next 3D image shows what happens when a ridge is “stuck” over a region.

Mountain Subsidence

When the Pacific Northwest has a heatwave a trough of surface low-pressure moves to the coast from California. This produces easterly winds, as you see in this next image. These winds climb the Cascades. As this easterly wind pours down the west side of the Cascades it compresses creating more heat. Hence the weirdly higher temperatures in Portland and Seattle.

If you look carefully at the wind graphic you can see why Astoria and rest of the coast got so hot.

The eastern Pacific has been slowly but steadily heating for years now. This heating and the gradual thinning of the marine layer means we have lost some of our natural air conditioning as cool marine layer moves inland. That makes events like this more pronounced.

Changes in heat waves

Incidentally, a large body of research indicates that severe heat waves are increasing in frequency, duration and intensity. Major cities averaged two heat waves per season in the 1960’s versus six per season in the 2010’s.

Looking at the big picture

This heat wave is a continuation of the trend toward increased upper-level blocking even in the warm season and the cumulative effects of a succession of large amplitude waves in the warm season that used to be rare. In short, more heatwaves.