by WeatherFlow meteorologist Shea Gibson

Ever been out on the water and notice there are systematically stronger areas of wind than others? Why would the wind be higher near sandbars/shallow waters than right at the beach? Why would there be strips of wind that seemingly follow the same tributaries or spit functions as water does? Let’s take a good look into something I’d like to call “Wind Rivers” or even could be called “Wind Streeting”.

As kiteboarders, we have the ability to harness the raw power of the wind in our hands (as do many others who ride almost any time the winds come up). Part of the experience is learning when to power and de-power the bar as wind pulses up-and-down. This helps to control speed, balance and ability to go upwind. One thing many kiters have run into here in the Charleston area is a phenomena where winds are consistently higher in certain spots vs others. It’s where you always have to depower the bar as that extra “kick” pulses into the kite. Many factors control this – such as directions, sea surface temps, air temps and many of the complexities at the land-and-sea interface. However, on a good solid wind day, we can find areas where there seems to be “rivers” of wind that are a few to several knots higher then other areas.

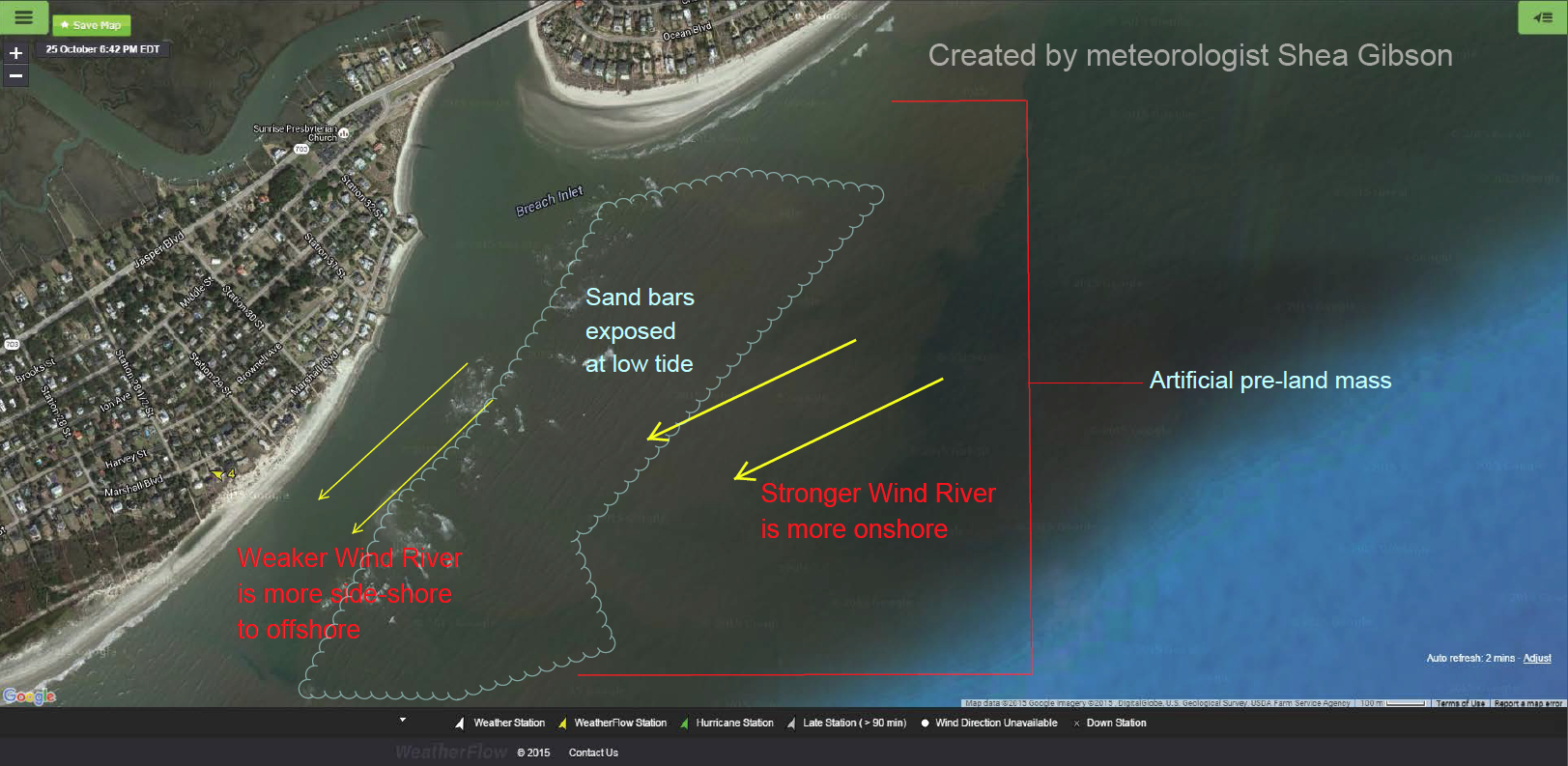

From my blog on ENE Seabreezes: We see that exposed sandbars help with accelerations. On several occasions, I (and others) have noticed that the winds are more onshore (Easterly) out beyond the sandbar..and become more side-shore (NE’rly) as we head in towards the beach. This makes it easier to get upwind on the outside, but harder to get upwind closer towards the beach. The tidal acceleration has a good bit to do with this as well, especially on an outgoing tide. However, there is absolutely a distinct shift..or “backing” of winds to the side-shore directions- and this could easily be due to the surface roughness guiding the surface winds in its direction. It’s almost as if the deeper waters are host to a less frictional ENE/EAST wind than the shallower waters, which tend to gain surface friction from increased shallow water chop.

Here is a good example of what we might experience on any given NE–>ENE event. Isle of Palms is the island at the top, Breach Inlet then Sullivan’s Island to the left. Then yellow arrows represent the directions winds are coming from.

**One important note: Once the sand bar becomes completely covered up by high tide, the wind direction pretty much becomes fairly uniform while the gradient weakens, resulting in the “drying up” of these wind rivers.

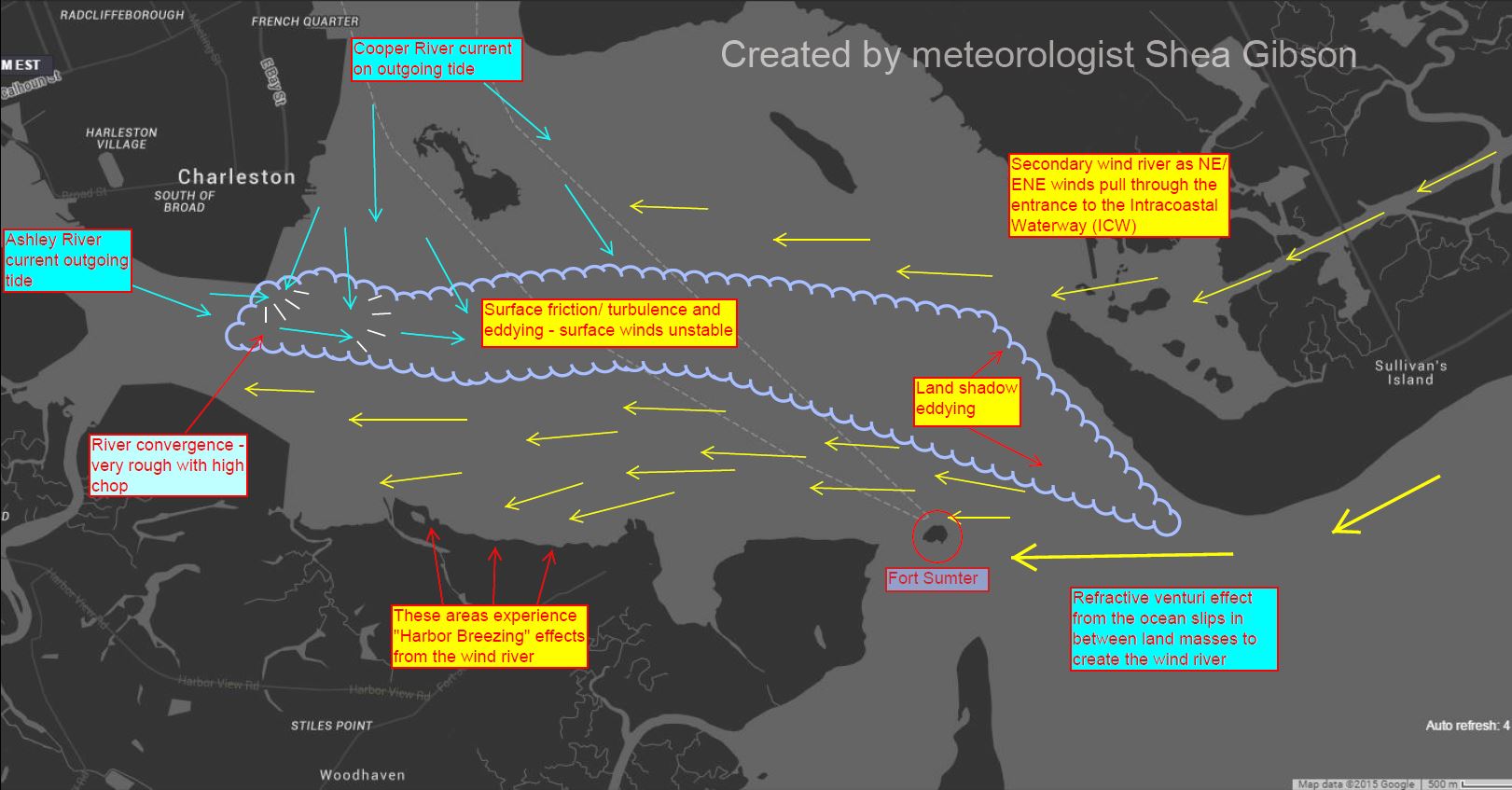

As we head into the Charleston Harbor during these directions, things get a bit more complex as land shadowing, river convergence and surface friction cause eddying and instability in the wind field. This divides the harbor into two sections – one for the main wind river pushing through in off the ocean…and a secondary wind river from the winds funneling down the Intracoastal Waterway. Here is a map of what is occurring on an outgoing tide. The wind rivers widen just a bit on an incoming tide as surface friction calms down.

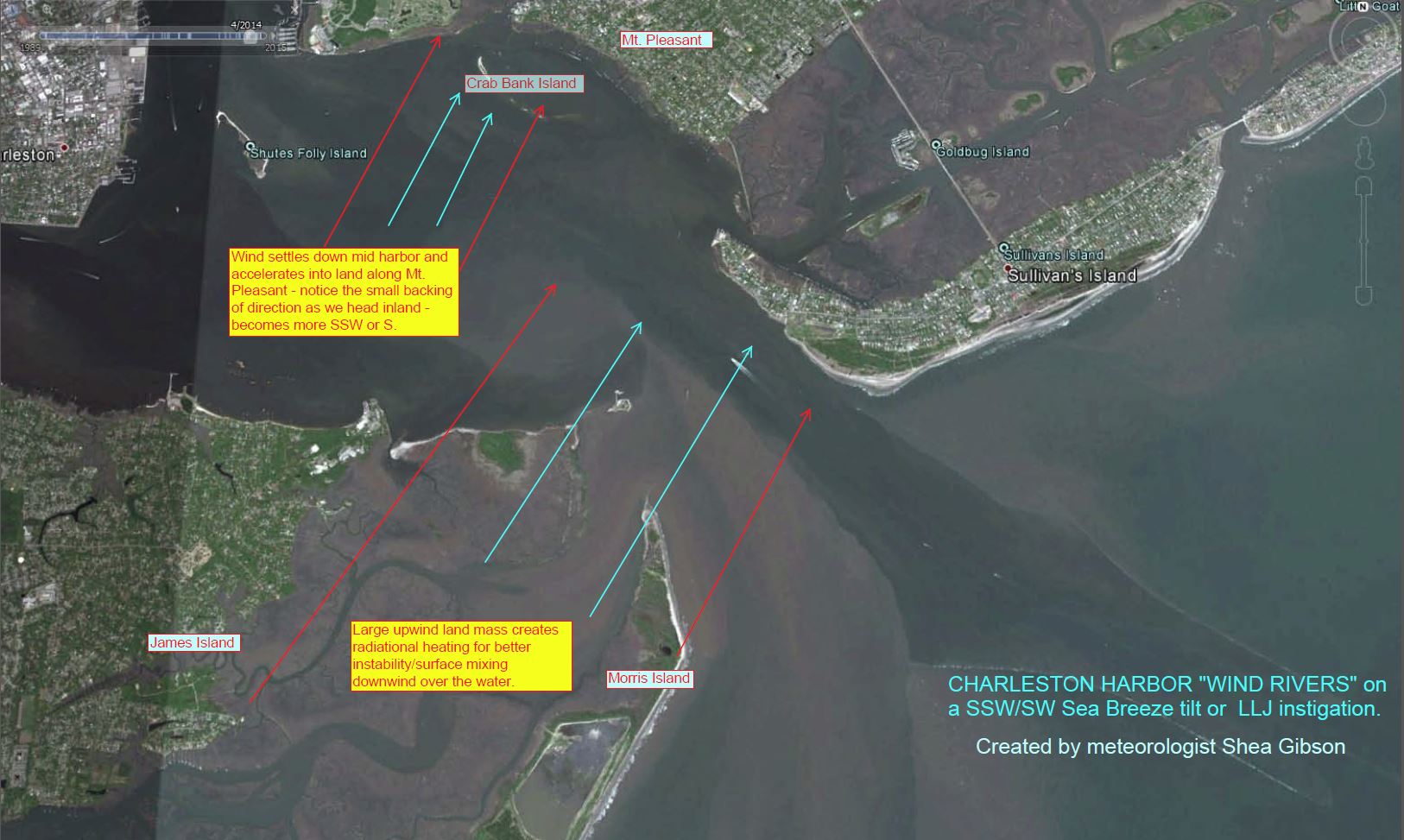

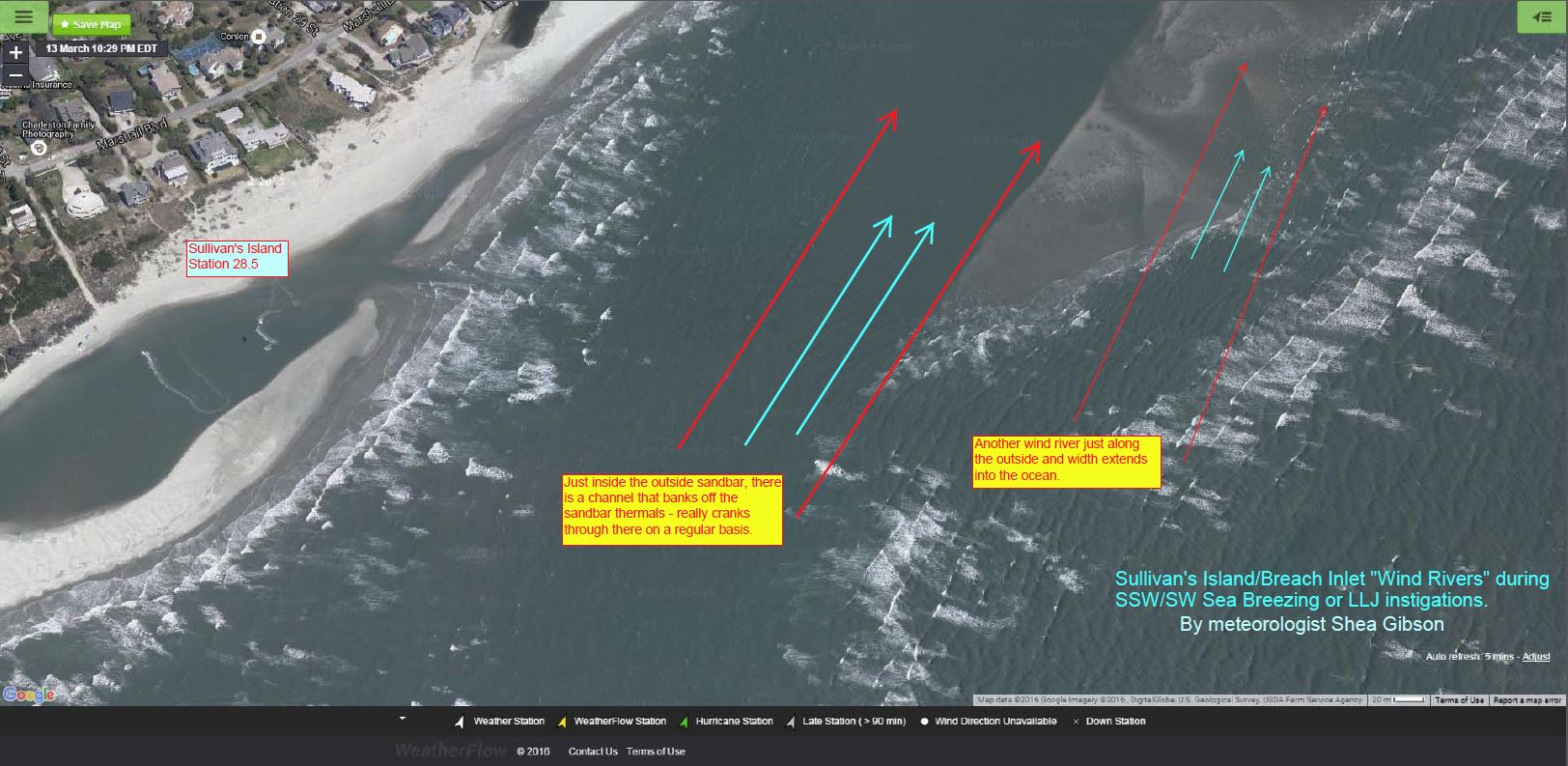

Here are the wind rivers during S–>SSW/SW Sea Breeze circulations (Coriolis shifting) and also applies to most instances of Low Level Jetting instigation where no Sea Breeze circulations exist…or the combination of both with coupling of the two.

Charleston Harbor – our Fort Sumter sensor regularly picks this one up as upwind warmer land masses allow for better surface mixing/instabilities.

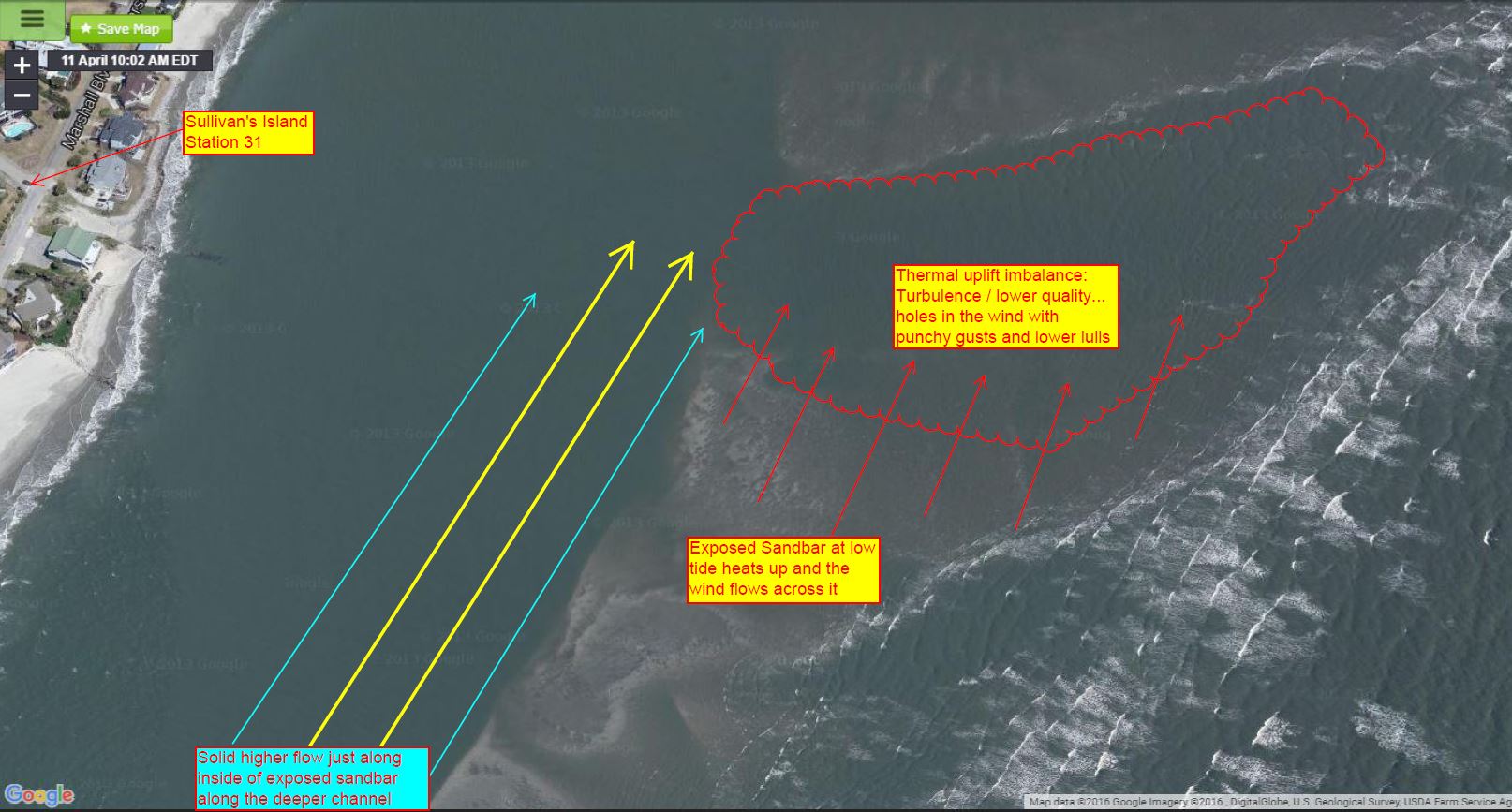

Sullivan’s Island beach and sand bar activity near Breach Inlet:

UPDATE 4/11/16: This past Friday, April 8, we had a solid SW Sea Breeze at 20kts to the beaches. Great time to put this to the test once again. As I rode my kite between the sandbars, I felt the heat being generated and blown into me. The wind instantly got holes in it and was significantly lighter with lulls-to-gust being wider. As soon as I made it just to the outside, it picked back up gradually, but not as strong as that area just inside the sandbar. Others riding with me in that area also confirmed their experience with this as well.

So what is causing this along our sandbars?

One theory involves dynamic mixing near these exposed surfaces at lower tides. The composition of the fine particle sand retains quartz and iron , which allow for rapid heating when the sun is out – especially when the ambient air temps rise to hotter temperatures. We all know too well the ‘ole RUN RUN! while walking these paths in the summer with bare feet- which I personally have experienced excruciating pain before reaching the beach. The focus is to run to the whiter piled up sand to cool the feet as the other lighter, coarser grains stay atop as winds blow it along into small bumps and dunes (wider granular profile and lighter weight for blowing).

Example of a cross section of what would be on a sandbar (pic from http://coastalcare.org/2015/05/what-the-sand-tell-us-a-look-back-at-southeastern-us-beaches-by-orrin-h-pilkey-william-j-neal/ )

And a better look at those irons and grains that retain heat- also from http://coastalcare.org/2015/05/what-the-sand-tell-us-a-look-back-at-southeastern-us-beaches-by-orrin-h-pilkey-william-j-neal/ – keep in mind that as sand bars dry, the whiter sands are stripped from the top and the darker colors are revealed (heat retaining).

Well – that very heating process helps create instability right along the sandbars – especially when the bars are directly upwind or side-side with the direction of the wind…or visa versa. This radiant mixing feature helps bring winds up in the immediate vicinity, where we experience anywhere from 2-5kts extra in those zones.

Another theory is that surface friction relaxes as waters ebb and overall swell height drops, thus leaving a cleaner surface to travel along.

We could even speculate that there is a compression of wind into the slightly elevated beaches along the dunes and homes all along the front line keeping winds pushed back, creating a highway of wind where the path of least resistance is- which is towards the coastal breaks and spits.

So should we call it “Wind Rivers”? Maybe Wind Streets or Wind Streeting? Does it need to be more technical to scientific terms such as “Thermally Induced Limited/Non-Limited Mixing Zones”? Will be sharing with some in the weather community to see what their thoughts are.

**** For now as of 4/11/16, I’m leaving this blog open for additional information after speaking with our mets team and others (and likely coastal geology experts from the College of Charleston for their thoughts) *****

Cheers!

Shea Gibson

WeatherFlow Meteorologist

Outreach/New Station Projects

SE Region/ East Coast

Twitter: @WeatherFlowCHAS