By WeatherFlow meteorologist Shea Gibson on June 30, 2015.

In this blog series, we explore the vast realm of Sea Breezes. What are Sea Breezes? How do they work? What would they look like if I could see them? Is there only one kind? How do you forecast for them? These are the questions we hear frequently and these are the questions we constantly have to ask ourselves when we look over the region on a daily basis.

The first question is “What are Sea Breezes?” By definition: The breeze that blows from the sea toward the land during the day, as air rising over the warmer land is replaced by cooler air from above the sea. Now other than being winds that blow in off the ocean, they are very complex in nature and require specific sets of criteria for the various speeds they are able to generate. The land-sea interface is very unique and very sensitive to the temperatures of both land and water. You’ve probably been out at the beach and noticed the winds almost dead calm and then all of a sudden they crank up out of nowhere without storming present…or a slower more gradual build until the sand is seemingly starting to cut you off at or below the knees. Or at other times you see clouds building and storms issuing out their rumbles…but never make it to the beaches. This leads us to the next question…

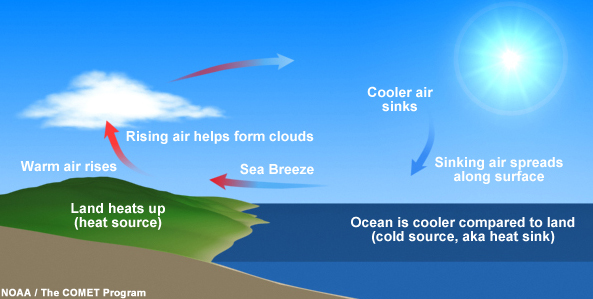

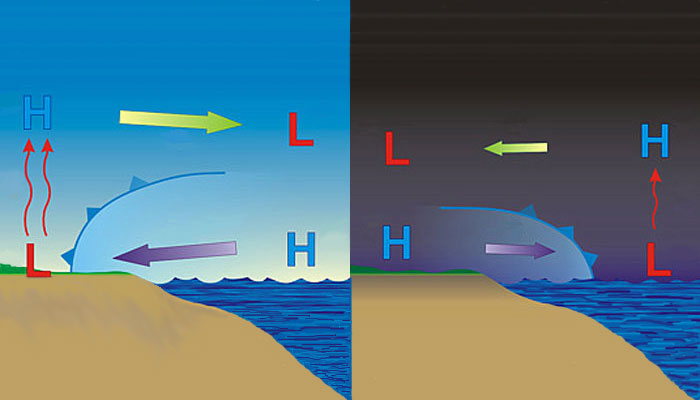

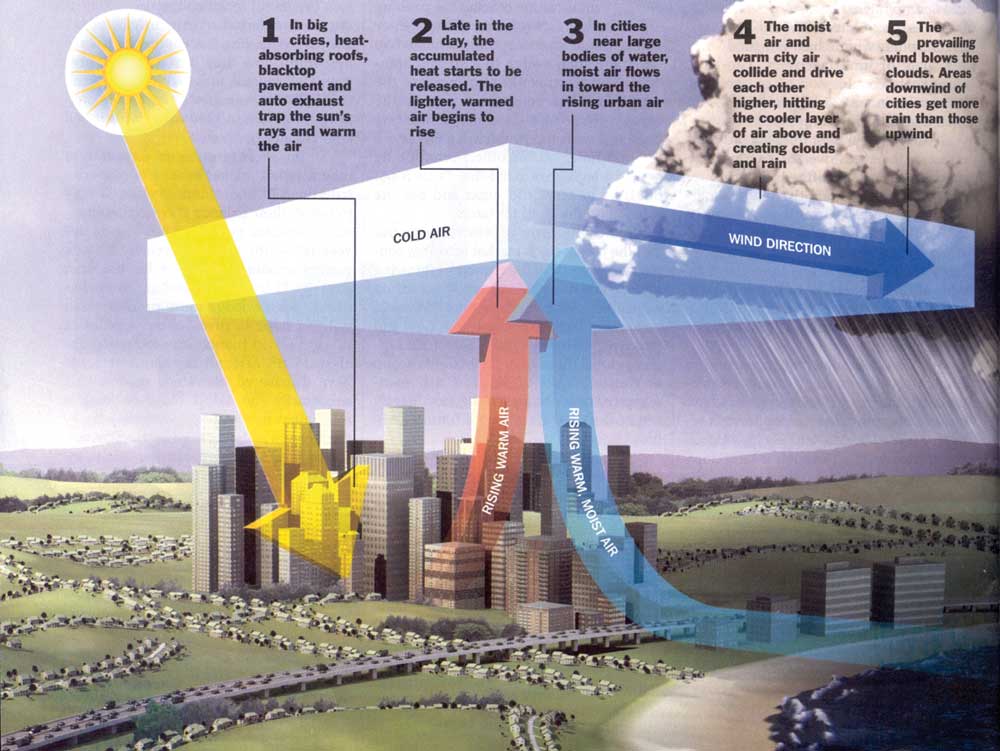

“How do they work?” First let’s take a look at what a typical setup is for the SE coastline: The Sea Breeze is in all actuality, a really unique type of cold front. In most cases, it sits offshore at night while land breezes (offshore Westerly winds down-sloping the elevations of NC, SC and GA) are generated from land cooling faster than the water. As the sun rises and the land heats (especially during our hotter months), the Sea Breeze “front” advances onto land and penetrates inland. The distance varies with the overall atmospheric profile of the area at the time, which is rarely the exact same from day to day. As the front advances, the warm air parcels known as “thermals” rise into the atmosphere from radiational heating (land heating) to help clouds build inland where low level moist air circulations mix with the hotter air along the head of the front. Additionally, urban heating over industrial zones, cities, asphalt parking lots, rooftops, etc… very often accelerate this process just inland or along the coast where air temps become significantly higher than what the normal temperature is. Now when we have heat rising and moist ocean air or inland residual moist soils from prior rains and/or moist vegetative areas inland, we will see low level circulations start to mix the two types of air to create large areas of instability – which creates convection. Opposing directions of mid level and upper level winds frequently drive these inland areas of convective clouding/storms towards the ocean, where they are met by the Sea Breeze front. This is known as the convergence zone and is an area of enhanced convective activity and/or thunderstorms. At the higher levels, the overflow of unstable air aloft pushes out as stabilized return flow back out over the ocean that cools, condenses and falls back to the surface…. which gets pulled right back into the Sea Breeze front again. This is known as a classic “Sea Breeze circulation”. Many times with a stronger Sea Breeze front, we see the inland storms get held back and explains why those storms sometimes never make it to the coast.

Here is a great pic from the NOAA/COMET Program that shows what I like to call the “coastal wind wheel”.

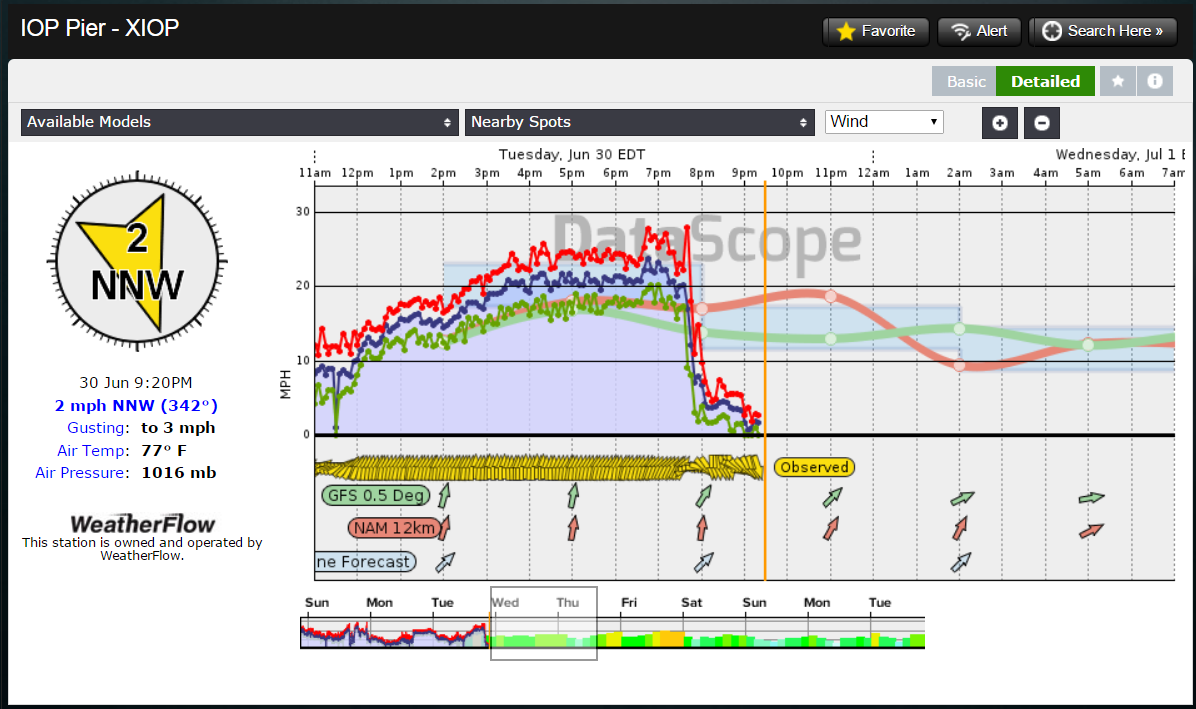

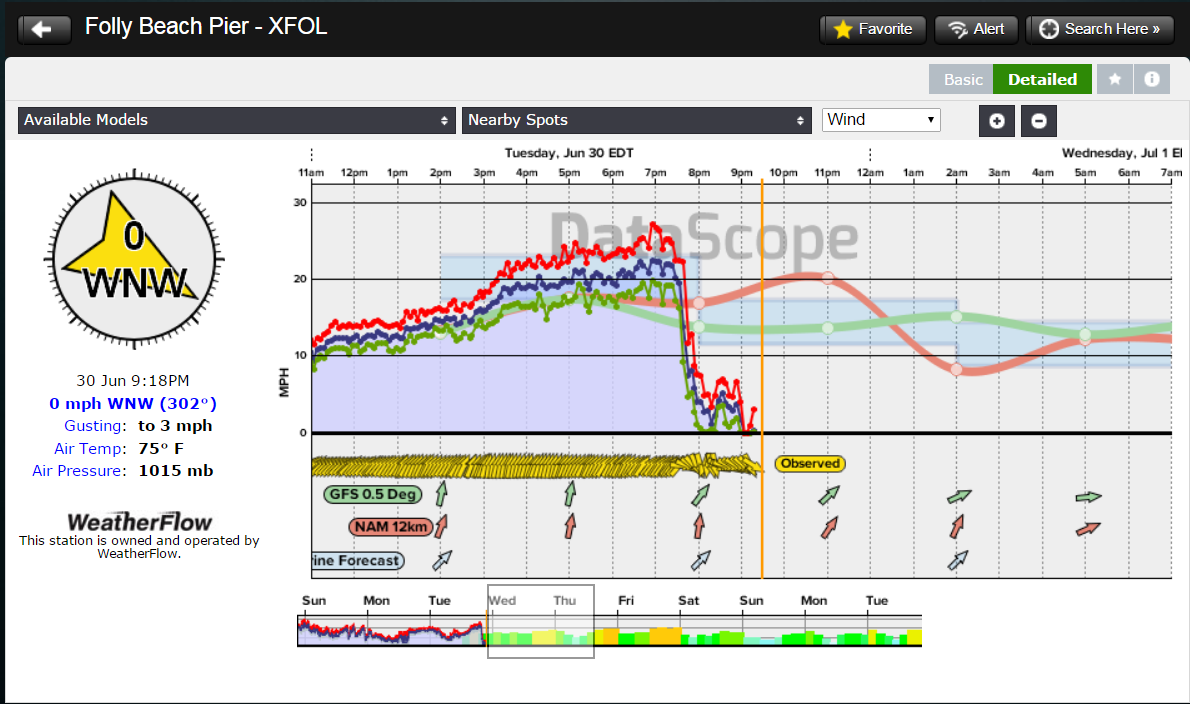

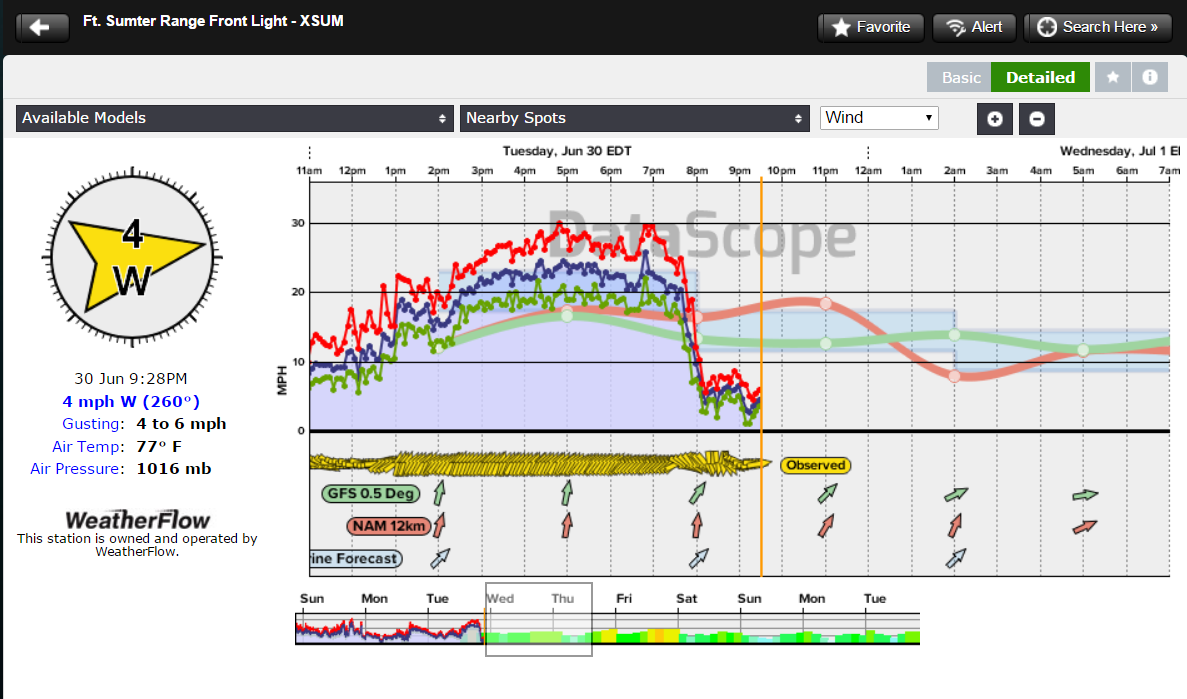

Winds from S/SSW/SW Sea Breezing along the coast today, June 30, 2015 up until inland storms breached the coastline in the evening.

Red = gusts , Blue = average and Green = lulls

Isle of Palms build was between 12pm and ~7:30PM before switching offshore.

Folly Beach’s build was between 11AM and ~7:30PM as well…

Charleston Harbor- neared 30mph in gusts. Notice the computer forecast models were quite a bit lower on their predictions.

Here are examples of the urban heat island effects – which is why sometimes the Sea Breeze convergence zone can show heavy rains in one specific area and half a mile or less away, we see little to no rain. Charleston’s UHIE signature is relatively small, but growing.

Coastline view:

Now we have a very broad coastal plain at sea level for GA/SC and Southeast NC. As we head inland, the elevation increases very gradually instead of abruptly, which allows the Sea Breeze to penetrate further inland. This explains why our thunderstorm lines develop so far inland up to 20-30 miles at times. This is called the “I-95 Corridor” from south GA into Hilton Head, SC. For Charleston, SC, I can say after living here for so many years and making observations, Peninsular downtown Charleston is a hot bed of activity, as well as Rivers Avenue/North Charleston as the true “Thunderstorm Alley”. To the north of Charleston, it’s pretty much up Highway 17 where storms are fed by urban commercial/residential heating downwind to Awendaw, McClellanville – and ultimately follow Highway 17 North up into NC, where inland Sea Breeze frontal surges follow the inside curves of the outer capes.

Here is the Sea Breeze front has penetrated inland along Southeast NC…where the dryer more stable air is behind it along the coast and the convergence zone is relatively quiet (at that time).

And a great .gif animation of the Sea Breezes stretching from NC down through SC. On some days, we can see this line stretch from northern FL all the way up into OBX.

Here is a snapshot I took in North Charleston, SC right along the vicinity of the convergence zone. 1st pic is facing South towards the ocean – notice the clearer and pleasant weather (pretty much clear past the bridge). In the 2nd pic, immediately to the west and north at the exact same time, you can see the convection building. Those clouds are heading towards the ocean and stalling directly overhead.

Another look inland of Folly Beach/Morris Island, SC at the build-up over West Ashley over to North Charleston. Pic by C-17 Air Force Pilot Sam Johnson (thanks again Sam!).

Ok so next we talk about the counter-part to the Sea Breeze – which is called the “Land Breeze”. At night, land cools faster than the water (radiational cooling) and the winds switch to offshore Land Breezes – or in most cases for GA/SC/NC we see some sort of Westerly wind overnight. The warmer air above the water continues to rise, and cooler air from over the land replaces it, creating a night time breeze. Depending on the amount of cooling, winds could be light to moderate. These are typically stronger during seasonal shifts in the fall and spring for the Southeast. Weaker in the summer months where low temps peak in the 80’s.

Video below shows the general ebb and flow of Sea Breezes to Land Breezes…and back.

Ok so that does it for what the Sea Breezes are and how they basically work. Next part in the series, I will dive into the other questions of “What would they look like if we could see them?”, “Is there only one kind? and “How do we forecast for them?” I will show the anatomy of the Sea Breeze front and break down the types of Sea Breezes (yes we have 4 types believe it or not) as we progress through this series.

Stay tuned 🙂

Cheers!

Shea Gibson

WeatherFlow Forecasting Team

SE Region/ East Coast

New Station Projects/ Outreach

Twitter: @WeatherFlowCHAS

UPDATE:

Part II: https://blog.weatherflow.com/sea-breezes-in-the-southeast-region-part-ii-types-of-sea-breezes/

Part III: https://blog.weatherflow.com/sea-breezes-in-the-southeast-region-part-iii-development-and-anatomy/

Sources:

http://www.classzone.com/books/earth_science/terc/content/visualizations/es1903/es1903page01.cfm , http://www.wmo.int Sea breeze: Structure, forecasting, and impacts Authors S. T. K. Miller, B. D. Keim, R. W. Talbot, H. Mao

Coastal pic from AF Capt Sam Johnson

NOAA/COMET Program